- Home

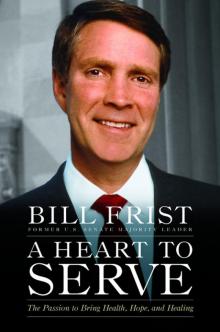

- Bill Frist

A Heart to Serve

A Heart to Serve Read online

Praise for A HEART TO SERVE

“Few men have lived a life as remarkable as this! Bill Frist’s story—from crude operating rooms in the Sudan to the highest post in the U.S. Senate—provides unique perspectives on many of the major issues of our times.”

—Frederick W. Smith, chairman and CEO, FedEx Corporation

“Dr. Frist is an extraordinary individual. Nurtured in a family that modeled the values of common sense, hard work, love for country, and compassion for those who are hurting, [he] has resisted being intoxicated by his great success—first, in the operating room as a heart transplant surgeon, then more recently in the halls of power in Washington. Instead, he has consistently chosen to serve others…. A HEART TO SERVE will inspire you to… become—like Dr. Frist—a force for the good of others. I heartily recommend this book.”

—Franklin Graham, president, Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, Samaritan’s Purse

“Doctor Frist’s message is simple: Discover your passions, then use them to serve. Part insider’s account of the Senate, part captivating storytelling, part personal revelation of how values color leadership, this compelling book is a clarion call to action to figure out how we can best serve. From the accounts of anonymous mission work in Sudan, the dramatic emergency response to the shooting of General David Petraeus and Capitol police officers, to a mother’s quiet gifts and a brother’s dream of serving millions through health care, the reader is inspired by the potential and power of service.”

—Senator Orrin G. Hatch

“Dr. Frist leads us on an engaging journey of principled action through a life of leadership grounded in family and community values. Thank God that we have humanitarians like Bill Frist to lead and bring awareness to worldwide poverty.”

—Jerry West, former NBA all-star and executive

“As a heart surgeon colleague, I have profound insights into Senator Frist’s expertise inside your chest, yet I am even more impressed by the passion burning inside his. Learn about leadership from one of this nation’s great public servants.”

—Mehmet C. Oz, MD

“Bill Frist reminds us all in this compelling book that politics and public service are about far more than winning elections. They’re about the commitment, compassion, and courage that good leaders bring to the noble causes they pursue. Bill Frist had those qualities in abundance, and the United States Senate was a better place because of him.”

—Senator Edward M. Kennedy

“A wonderful collection of inspirational examples of leadership, public service, and compassion for others.”

—General David H. Petraeus

“Whether he’s in his surgeon’s mask in a hospital in Uganda, or in cuff links in the marbled halls of DC, Bill Frist is working hard to save and improve the lives of the poorest people on the planet. He’s an inspiration.”

—Bono, lead singer of U2 and co-founder of the anti-poverty advocacy organization, ONE

“In A HEART TO SERVE, Bill Frist draws upon his family legacy, his personal faith, and his experiences as both a cardiothoracic surgeon and a United States Senator, offering readers a sincere self-portrait of one of our nation’s most dedicated leaders in health care policy.”

—President Bill Clinton, founder, William J. Clinton Foundation, 42nd President of the United States

Copyright

Copyright © 2009 by William H. Frist

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Center Street

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

www.twitter.com/centerstreet

Center Street is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Center Street name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: October 2009

ISBN: 978-1-59995-146-1

Contents

Praise for A HEART TO SERVE

Copyright

1: Mission of Mercy

2: A Legacy of Caring

3: A Family Like No Other

4: Breaking Away

5: Karyn

6: The Heart of the Matter

7: The Unlikely Candidate

8: New Kid on the Hill

9: Capitol Crossfire

10: A Frightening New World

11: Unexpected Storm

12: Getting It Done

13: When Push Comes to Shove

14: A Promise Kept

Acknowledgments

Notes

1

Mission of Mercy

The single-engine ten-passenger Cessna Caravan dipped dangerously low, a mere four hundred feet above the large trees and sparse brush dotting the sands of southern Sudan. I could feel the African heat rising from the earth below. I was flying under the radar to avoid detection by the Sudanese government’s high-flying bombers and the fourteen ominous helicopter gunships they had stationed at nearby Juba.

Our circuitous journey had begun more than six hours earlier, just before sunrise, in Nairobi, Kenya. There we had filed an ambiguous flight plan so no one could track our plane. We were flying into Sudan clandestinely, without permission and decidedly against the will of the regime in Khartoum, which the United States had formally designated as a supporter of terrorism. Since the United States had no diplomatic relations with the huge African country, we had no passports, no visas, and no official documentation. Nobody in the U.S. government knew our whereabouts or our intentions. Though our plane was full of medical supplies and we were on a mission of mercy, we were sneaking into the Islamic Republic of Sudan at our own risk.

We flew first to Entebbe, Uganda, landing just in front of the old, bullet-pocked terminal—the scene, some twenty-two years earlier, of the famous 1976 Israeli commando raid that liberated nearly one hundred Air France passengers and crew members who’d been taken hostage by Palestinian terrorists. We quickly refueled the Caravan and headed northwest to Bunia in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Then we veered north and dropped to barely above tree level, surreptitiously entering southern Sudan.

We were on our way to the remote region called Lui (pronounced Louie), about a thousand miles south of Khartoum, Sudan’s capital city, and five hundred miles west of the Nile. There, a makeshift medical clinic had been opened a few months earlier by Samaritan’s Purse, the Christian-based humanitarian relief organization headed by Reverend Franklin Graham. No more than an old schoolhouse with one doctor and a few Sudanese assistants—brave and willing, but with no formal medical training—the clinic at Lui was the only medical facility for half a million residents in that part of Sudan.

For the six of us in the Caravan, it had already been an arduous trip, and the element of risk loomed larger as we approached our destination. We were flying into the midst of an ongoing civil war between northern and southern Sudan. The National Islamic Front that controlled the Government of Sudan (GOS)—the same government that harbored Osama bin Laden for five years—was conducting a scorched-earth policy in an effort to wipe out the black African Christians, animists, and non-Arab Muslims living in southern Sudan. In response, a rebel movement known as the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) had emerged in the early 1980s.

It wasn’t easy to distinguish the good guys from the bad guys in this war. They were fighting over water, potentially massive oil reserves, and political clout, their battles fueled by racial and religious resentments. But story after horrible story bore witness to atroci

ties by the Khartoum regime. The GOS tortured and killed indiscriminately, raping women and young girls repeatedly, and forcing men, women, and children into slavery. Although I couldn’t condone everything the SPLA had done, I sympathized with the people of southern Sudan and their plight under the persecution by the regime in Khartoum, and I had come to know their popular and charismatic leader, John Garang (who subsequently became a close friend), and his ragtag rebels who opposed the forces of the GOS and its terrorist-sponsoring president, Omar al-Bashir. Nevertheless, the medical team of which I was a part was committed to providing medical care to anyone who needed it.

At the time of my first trip to Lui, in early 1998, the civil war had dragged on for more than fourteen years. War had pushed the population into areas where food and water were sparse, leading to widespread famine and disease. More than two million people had already died. A recently intensified aerial bombing campaign by the GOS had forced millions more to flee their homes, abandoning their small patches of farmland or traditional cattle grazing areas.

In Lui, the primitive hospital and a tiny church were practically the only permanent structures, and both buildings were frequent targets of GOS bombardment. This was especially galling, since some of the government’s own Islamic troops, captured by the rebels, had been treated by doctors at the facility.

Although I was a sitting United States senator, I was traveling to Sudan as a private citizen—a physician by trade—on a medical mission sponsored by Samaritan’s Purse. I’d been invited by Dr. Dick Furman, a general and thoracic surgeon from Boone, North Carolina. He and his brother Lowell for years had taken a month off each year to volunteer their services to fill in for full-time medical missionaries in the developing world. Soon they were recruiting other surgeons to do the same, then medical doctors, nurses, and technicians. Their idea grew and grew, becoming World Medical Mission, a faith-based organization committed to sending hundreds of doctors each year to Third World countries, including some in the most dangerous parts of Africa.

I’d met Dick through my older brother, Bobby, who’d trained with Dick during surgical residency at the University of Kentucky in Lexington. Later, Dick and his wife, Harriet, would visit Bobby and his wife, Carol. During my medical school years, I would join them and listen to the fascinating stories about Dick’s mission trips around the world. The stories reminded me of the time when our dad had taken a medical mission trip to Mexico, using it as a springboard to found a Presbyterian-based medical mission foundation. Maybe someday, I thought, I’ll be able to help people around the world, too.

As for Franklin Graham, I’d met him only once before my first trip with World Medical Mission. I was coming off a plane in Nashville during my 1994 campaign for the U.S. Senate, and we recognized each other. Both of us are pilots, so we talked planes for a while. He told me that he’d just received the gift of a plane for Samaritan’s Purse from the head of the Tennessee Democratic Party. Since I was working night and day to unseat a Tennessee Democrat at the time, the last thing I wanted to hear about was the kind deeds my opponents were doing! But then again, Democrats and Republicans are in this world together trying to make it a better place—though with different approaches, for sure.

Now Dick and I were making our way across sub-Saharan Africa on a mission sponsored by Franklin’s organization. At the time, few had taken up the cause of the people of Sudan. The major media had barely mentioned their plight, and nobody dared risk flights into southern Sudan—nobody except gutsy, devoted pilots like the man sitting next to me, Jim Streit of AIM AIR, a church-supported group flying out of Nairobi and other mission bases around the world. Jim and his fellow pilots are a rare breed. They could easily be earning six-figure salaries flying commercially in the United States, but instead they choose to serve for paltry wages in some of the most dangerous areas of the world.

Accompanying us to Sudan were Robert Bell, an executive with Samaritan’s Purse; Scott Hughett, Samaritan’s Purse special projects coordinator and Dick’s son-in-law; and Kenny Isaacs, who’d pioneered Samaritan’s Purse’s efforts in Sudan. And in a passenger seat behind me was David Charles, a young neurologist from Nashville. David had recently completed his residency at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and joined me as a policy fellow for a year in my Senate office in Washington. As I glanced back at him during the flight to Lui, I wondered whether David was questioning the wisdom of his decision. Little had he known when he’d come to Washington to study policy that two months later he would be flying with me into the bush country of war-torn Sudan!

Now the plane dipped still lower. Up ahead, just beyond a clearing, we saw a makeshift airstrip—little more than a stretch of graded dirt, just long enough to bring the Caravan to a stop. A battered jeep sat next to the landing strip, and a lone fellow stood nearby, holding a cane pole with a plastic bag tied to one end—our wind sock.

I circled the field to make sure the runway was clear of animals, then quickly brought the Caravan down for a short-field landing. No sooner had we hit the ground than I turned around and saw David’s face. He was pale as a sheet yet dripping with perspiration, his eyes wide with anguish.

Thinking the bumpy ride (the last hour had been at 400 feet above the treetops to avoid detection from the air) and heat had gotten the best of David, I called back to him over the noise of the plane’s engine, “David, are you doing okay?”

“No!” he shouted, pointing out the plane’s window. “We’re all going to die!”

I followed David’s stare and saw a stream of ragtag camouflage-uniformed soldiers running out of the bushes and directly toward the plane from every direction. They looked young, almost like teenagers, but they were all brandishing Russian-made AK-47s, many raising their rifles high in the air as they approached. Regardless of their age, these boys were obviously not to be trifled with.

What did they want? Did they plan to attack us and destroy the airplane? Were they members of the Sudanese government-sponsored militia, about whom we’d been emphatically warned? We had no idea. Worse yet, we had no recourse but to watch and wait. If we tried to turn around, taxi back down the airstrip, and take off again, we’d be an easy target. With so many guns, one of them was bound to bring down our plane.

I looked back at Dick and Kenny. “Are we in the right place?” I asked.

“I sure hope so,” Dick deadpanned, before cracking a hint of a smile.

For a few long seconds, we simply sat there, watching the throng of dirty, disheveled soldiers drawing ever closer to us. None of us was armed, and even if we had been, any attempt at a firefight would have been futile. David bowed his head.

A few more seconds passed; large drops of perspiration dotted our foreheads, and only partly from the intense African heat. Finally, Kenny, who was the only one of us who had been to the Sudan before, broke the silence with a joyful yelp. “Yeah, yeah,” he said, his face pressed against one of the plane’s windows. “These guys are on our side!”

“What?” someone gasped.

“Yeah, they’re friends,” Dick agreed. “I think they are here to protect us, not to hurt us.”

Despite Kenny’s and Dick’s reassurances, we took our time opening the plane’s doors. Sure enough, as we climbed out, we were greeted by the warm smiles and friendly faces for which Africa is famous. We tried not to notice the arsenal of AK-47s.

We quickly set to work unloading the food, water, and medical supplies we had brought along—bandages, surgical instruments, medicines, cots, tape, syringes, anything we’d thought we might need. Time was of the essence. Our protectors pitched in, stacking as much as possible in the jeep or on their backs, while Jim Streit refilled the fuel tanks from a fifty-five-gallon drum that we had brought with us. In a few moments, Jim was back in the cockpit, and the Caravan’s propeller cranked up again. Before we’d finished loading the jeep, the plane was already taxiing down the bumpy airstrip. To remain any longer would be to invite a visit from the GOS’s roving Antonov bombers.

<

br /> Surrounded by the teenage soldiers, we watched as the plane lifted into the sky and headed back toward Nairobi, whence we’d come. I thought, There goes our lifeline to safety. No cell phones, no radio, no communication. We were on our own.

* * *

OUR ARMED HOSTS ESCORTED US A BUMPY FIVE MILES TO WHAT HAD once been the village of Lui. The dirt road was laced with landmines, and occasionally our driver took a wide sweep around a warning marker in the middle of the road. We passed the old hospital, a one-story structure that had been bombed out and deserted for more than a decade, with landmines placed all around it during the recent war just to make sure that no one tried to resurrect it.

A little farther on, we saw the new “hospital,” actually an abandoned schoolhouse with the roof blown off. Since the war had started nearly fourteen years ago, it had been far too dangerous for children to attend school. Consequently, an entire generation of young people had grown up with little or no education.

The school, the original hospital, and the town’s first church had all been built by a remarkable and still-revered missionary doctor, Dr. Kenneth Fraser, who’d arrived in Lui in 1920. In the mid-1800s, Lui had served as a regional slave-trading center, and Dr. Fraser and his wife launched their mission work under the very tree where slaves had once been sold. Dr. Fraser’s writings describe how, shortly after arriving in Lui, he performed emergency surgery on a tribal leader’s son who had been attacked by a lion. By saving the boy’s life, Dr. Fraser won the respect and acceptance of the formerly distrustful villagers. In time, he grew his mission to include a medical facility, then a church, then a school, and eventually a prospering village. Dr. Fraser, whose gravesite behind the church is still respectfully visited today, saw healing built trust, something we would experience in a similar way eighty years later.

From the late 1980s and through the mid-1990s, war decimated the village. Those who were not killed were driven off or were living in the bush. Through arbitrary bombings and surprise ground attacks, the GOS prevented the displaced villagers from mounting any resistance or resuming normal life. What remained of the village had been under government control until about two years before our arrival, when the SPLA finally drove out the government troops. As mentioned, the entire area around the old hospital was still laced with landmines, buried there either by the GOS troops or by local SPLA rebels. The landmines killed so many that the former residents feared returning. Lui was a ghost village.

A Heart to Serve

A Heart to Serve